Annual Public Health Report 2024

- Foreword Cllr Ruth McEwan

- Foreword by the Director of Public Health

- Introduction – public health comes home

- The organised efforts of society for public health in Reading

- A vision for public health in Reading

- Our priorities

- The strategic context

- The way ahead

- Where are we now?

- Section One: Health Protection

- Section Two: Health Improvement – Adults

- Section Three: Health Improvement – Children and Young People

- Section Four: Healthcare Public Health

- Section Five: Public Health Delivery Support

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

Foreword Cllr Ruth McEwan

Primary prevention is an important term in the world of public health.

Its broad definition would be ‘lowering the incidence of disease and health problems by reducing lifestyle risks and their causes or by targeting high- risk groups’.

But in plain terms, it means stopping health problems before they start. Like all public health teams nationwide, this is an overriding goal for us in Reading, which makes children and young people a hugely important demographic for our work.

But it won’t be an easy task.

In Reading, we face numerous challenges to provide the support children need to thrive as they grow and develop, and to iron out the health inequalities that exist. And, like most areas of the country, Covid-19 has disproportionately impacted Reading’s children – in physical and mental terms – at a crucial stage of their lives.

But, as you’ll read in this report, we’re working hard to counter these challenges and give our children the best possible start in life.

The Healthy Child Programme is doing an outstanding job to support parents and carers, promote child development and improve child health outcomes. Commissioned in partnership with West Berkshire and Wokingham local authorities and delivered by Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, this service provides school nursing and health visiting services for all children resident in Reading.

We also work closely with colleagues across the council and the voluntary and community sectors to deliver services promoting the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people.

Improving the mental health of the population as a whole is also a priority area. We’ve put considerable resources into providing support and services for those who suffer poor mental health – including the ‘Z card’ and Wellpoint Health Kiosks initiatives. But we also recognise the importance of educating people on what leads to good mental health – again, taking a primary prevention approach.

In more broad terms, the Reading team’s public health programmes have made significant in-roads in tackling the health and wider threats posed by drugs, alcohol and tobacco.

However, more work needs to be done. Drug and alcohol use is closely linked with homelessness, poor mental health, unemployment, domestic abuse, and ill health, which means the impact is not only felt by the individual but also passed on to families and wider communities.

“Improving the health of young people, and instilling healthy behaviours, gives us the best chance of preventing ill health in later life and has the best chance of creating a healthier population.”

Ruth McEwan, Reading Borough Council’s Lead Councillor for Education and Public Health

Foreword by the Director of Public Health

It is my privilege to present the first public health annual report for the unitary authority of Reading Borough Council.

In previous years, reports have covered Berkshire as a whole, making this the first to focus exclusively on Reading.

In these pages, we have set out the ambitions of Reading’s public health team and outlined how we will work to improve the health and wellbeing of the local population and reduce health inequalities over the next three years. We also detail our current position and describe the recent work we’ve carried out in the context of the three pillars of public health – health protection, health improvement and healthcare public health.

The report highlights the importance of working with other teams in Reading as well as with individuals, communities, groups, bodies, and organisations beyond it. In the world of public health, we describe this as the ‘organised efforts of society’– a concept that plays a vital role in preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health.

This approach allows us to have a positive impact on the lives of more people and provides the opportunity to influence the wider determinants of health, such as education, housing, employment, the built and natural environment, our social and community networks, and the roots of crime and violence.

The report also focuses on high-quality evidence-based decision-making and strong communication – the book- ends of public health. Likewise, communicating effectively with local communities has been vital in our response to the Covid-19 pandemic and we will continue to build on this experience.

Commissioning and delivering public health services has been an important aspect part of our provision and will continue to be so. These include health visiting, NHS health checks, specialist sexual health services, substance misuse services, smoking cessation and weight management services.

Our workforce is also essential, with building the skills and capacity of the public health team and wider workforce central to delivering our ambitions.

“Evidence and intelligence underpin everything we do in public health and require a broad approach. This includes generating new knowledge from research, using new techniques to turn data into intelligence and designing services using the experiences of local people and communities.”

Prof. Dr John R Ashton C.B.E. Interim Director of Public Health Reading and West Berkshire

Introduction – public health comes home

This journey has its roots in a series of major societal developments and events.

These included radical changes in agriculture, industrialisation, the mass movement of people from the countryside to towns and cities and a series of cholera pandemics from Asia between 1836 and 1866 that decimated populations, not least in the urban slums.

Until that time, the role of local councils was a limited one, extending mostly to guaranteeing the security of residents and facilitating trade through the issuing of market licences and engagement with the business community. The response to cholera at the local level would lead to the extensive range of responsibilities that we associate with modern local government today.

The threat posed by the pandemics galvanised local action, not least through the development of a broad- based public health movement – a partnership of local politicians, businessmen, churches, and the local press, together with enlightened medical practitioners who were interested in preventing disease. In the vanguard of this movement was the Health of Towns Association, which sprang up following the publication of Edwin Chadwick’s ‘Report on The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Classes,’ in 1842. This drew attention to the high death rates in the nation’s slums. Until then, it was assumed that because the urban economy was booming, as a result of industrialisation, life was better for everybody in the towns compared with the countryside.

When the Health of Towns Association was formed at an inaugural meeting at Exeter Hall on the Strand in London, on 11 December 1844, it was described as “an avowedly propagandist organisation, of capital importance”. (1)

This was an early example of an evidence-based campaign to address the causes of avoidable death that disproportionately affected the poor. And it was the beginning of a tradition that has extended down the years via the Rowntree reports on poverty, to today’s Marmot reports on Inequality in Health.(1)

The first Public Health Act was passed in 1848 as a result of the Health of Towns Association’s work. This included: disseminating facts and figures drawn from official reports; organising public lectures on the subject; reporting on the sanitary problems of their district; and providing instruction on the principles of ventilation, drainage and civic and domestic cleanliness whilst campaigning for parliamentary action to give powers of intervention to local authorities.

This Act built on the innovative action of Liverpool in passing its own parliamentary ‘Sanatory (sic) Act’ in 1846, which enabled the town to appoint the country’s first full-time Medical Officer of Health. The 1848 Enabling Act extended this power to the many towns and cities that followed suit over the next 20 or so years until this became a requirement in the later Public Health Act of 1875.(2)

Annual public health reports, such as this, have represented not only a snapshot of population health in a moment in time, and a reference point for action, but are also documents of record for the future. This provides value to policymakers, practitioners and the public, and enables us to learn from the past, to see how far we have come and, hopefully, avoid repeating previous mistakes.

Reading Medical Officer of Health Report 1923 – Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer of Health, Reading County Borough

In 1923 when Mr H J Milligan, the Director of Public Health for the County Borough of Reading,

submitted his annual report to the Mayor, Aldermen and Councillors, the mid-year population was estimated to be 93,160. There were relatively low numbers of men in their midlife mainly due to deaths in World War 1. The birth rate was higher than the death rate and, even though infant mortality had been reduced by child welfare work,

it remained shockingly high at 51.6 per 1,000. However, unlike today, overall life expectancy was still steadily increasing mainly as the result of improved sanitary conditions. The structure of Mr

Milligan’s Public Health team reflects these priorities, with medical officers, sanitary inspectors, health visitors, tuberculosis nurses and matrons driving the work forward all supported by a team of clerks.

His report compared conditions with those from 50 years previously and also found that Reading compared favourably with other areas. Reading was observed to have a low birth rate and a low infant mortality rate. Maternity and child welfare

had also improved whereas it was noted that before the infant welfare movement began a death rate of over 10% amongst children had been tolerated

As is often the case, this valuable public health work was faced with criticism, which claimed much of it is “directed towards preserving the unfit”. Mr Milligan argued that “all the evidence indicates that not only is the number of survivors increased, but that they are healthier than their predecessors”.

A summary of infectious diseases reported epidemics of scarlet fever and measles with ongoing prevalence of diphtheria, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases. There were eight deaths from a severe outbreak of measles, four from whooping cough, and 109 from tuberculosis, with reports about various sanitoriums and relatively high numbers of cancers, heart disease and respiratory illnesses. There were 33 deaths from violence, including eight suicides.

Hygiene schools were another feature of the report with a sanitary survey highlighting problems with lighting, cleaning and ventilation.

In addition to comments about the design of buildings, it reported findings from routine examinations of school children at three points in their school lives.

One in ten children needed medical treatment for conditions ranging from ringworm, scabies and ‘uncleanliness of the head’ to defective vision and hearing and dental disease. Ninety-three children were referred for treatment of malnutrition and 16 for tuberculosis.

In 1923, there was an acute shortage of housing. And, of the 1,268 houses that were inspected, 814 were found to be unfit. That year, 131 houses were built, 20 of which were part of a municipal housing scheme that did not meet the needs of

working people. Two notices requiring defects to be remedied were served under the public health acts of the time and additional local by-laws – including the reading Corporation Act 1914 – provided powers to demand food storage accommodation in new houses and for the medical offer to examine the inmates of common lodging houses during outbreaks of dangerous infectious diseases.

Notably, the report includes an update on the nine beds in the smallpox hospital at Whitley Camp, one of five hospitals provided by the local authority.

The work of the early pioneers of public health – from the 1840s onwards – was organised around a principle that came to be known as ‘The Sanitary Idea’. This focused on the separation of human, animal and vegetable waste from food and water.

Twenty years before the germ theory of disease was discovered, this led to concerted action on sanitation, cleanliness, scavenging, street paving, safe municipal water supplies, street washing and slum improvement.

Over time, the credibility of local government increased as a result of its effective action in tackling epidemic disease through these measures.

Other programmes also became possible, including:

- The creation of municipal parks, giving access to fresh air and exercise for industrial workers on their day of rest

- Municipal bath and washhouses

- Municipal housing

- Other infrastructure initiatives such as gasworks and hygienic slaughterhouses.

The advent of mains sewerage systems, the mass manufacture of soap and new insights into the germ causation of infectious disease brought about a shift in focus from sanitation to hygiene from the 1870s onwards.

At the same time, personal health and social services such as health visitors, social workers, and community nurses began to emerge from their environmental roots in household inspection – again, based in local government. Initiatives included the health visitor movement that began in Salford in 1862; the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, in Liverpool in 1883; and the first depot to provide milk to nursing mothers, in St Helens, in 1899. Innovation and rollout by local councils came thick and fast.

Despite these advancements, the Boer War (1899-1902) brought the issue of public health to the fore as 40% of men who volunteered for service were deemed unfit to serve. As a result, concerns were expressed about how the nation would deal with the increasing military threat posed by Germany. An interdepartmental government enquiry into the“physical deterioration”of the nation led to a comprehensive programme of action:

- A continuing anthropometric survey

- Registration of stillbirths

- Studies of infant mortality

- Centres for maternal instruction

- Day nurseries

- Registration and supervision of working pregnant women

- Free school meals and medical inspection of children

- Physical training for children, training in hygiene and mother craft

- Prohibition of tobacco sales to children

- Education on the evils of drink

- Medicals on entry to work

- Studies of the prevalence and effects of syphilis

- Extension of the Health Visiting Service.

At the time, there were arguments over whether the community or the family were responsible for health and wellbeing – an echo of contemporary debates about the so called ‘nanny state’. However, the interests of the nation prevailed, and the School Meal and School Health Services was established.

Over 100 years on from the 19th century, the range of local government initiatives looks impressive and comprehensive. Sadly, it was not to endure in the face of scientific medical advances and the increasing domination of hospital medicine, as the therapeutic era, based on pharmaceutical and other technical interventions, took centre stage.

The widely accepted definition of public health was first coined by Charles Winslow, Dean of Public Health at Yale School of Public Health, in 1920: “Public Health is the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting physical health and efficiency through organised community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organisation of medical and nursing service for the early diagnosis and treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health”. (3)

This comprehensive approach attracted widespread support after World War 1, building on the Boer War report but being extended to include Prime Minister Lloyd George’s major programme of ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’.

When the Poor Law was abolished in 1929 – and its responsibilities, including for the relief of poverty and the workhouse hospitals, were passed to local government – the era of local government public health had reached a peak.

At this point, the Medical Officer of Health was responsible for:

- Traditional environmental services – water supply, sewage disposal, food control and hygiene

- Public health aspects of housing

- Control and prevention of infectious disease

- Maternity and child welfare checks, health visitors, community nurses and midwives.

He (sic) was also responsible for the tuberculosis dispensary and venereal disease clinic. Wearing his other hat, he oversaw school health, which included responsibility for the administration of the local hospital.(5)

Some of the larger public health teams consisted of thousands of staff.

What came next was a therapeutic era in public health, with major scientific advances, beginning with the discovery of insulin and the early antibiotics. Until this time, medical interventions made precious little difference to life expectancy and chronic ill health. Rather, the major improvements that had taken place – and had led to dramatic falls in childhood mortality and from water and food-borne infections – were down to:

- Improved living and working conditions

- Safe water and sanitation

- Increased agricultural productivity that had made cheap food abundantly available for the poor

- The adoption of birth control, leading to smaller families and less competition for scarce family resources

- The beginnings of vaccination for a range of infections.

Improvements also included the later BCG vaccination and medication to control tuberculosis, which, along with epidemic pneumonia, was described as one of the “captains of the men of death”.

The formation of the NHS in 1948 marked a dramatic change in emphasis with a widespread belief that public health had completed its historic task. It was believed that the future would be largely based around hospital medicine with ‘a pill for every ill’ and more ambitious surgeries thanks to antibiotics preventing wound infections.

This also marked the point at which medical careers in general practice sharply divided and both public health and general practice went into a sharp decline.

By the time of the major local government reorganisation in 1974, the public health workforce was demoralised and struggling to recruit. Also, other professional groups, such as social work, environmental health and community nursing, were vying for their own professional space, away from the hierarchical leadership by the Medical Officer of Health. As a result, the role was reinvented as an administrative position in the NHS – that of Community Physician – but it was to be short-lived.

The creation of joint NHS and local government posts to control communicable diseases began the transfer of public health back to its proper home in local government. However, it was to take 27 years, until 2013, before this was implemented in full.

In the meantime, the 1970s saw increasing global recognition that countries may be on the wrong path with their infatuation with hospitals at the expense of public health and primary care, and that a rebalancing was necessary. The publication of the Alma Ata Declaration by the World Health Organisation in 1978 called for a reorientation of health systems towards primary health care grounded in a public health framework. It argued for an emphasis on public participation and extensive partnership working, taking this thinking further by calling for cross-cutting policies that promote and improve health.

These initiatives implied that the approach to health had placed undue emphasis on the role of hospitals in improving health and that everyday maladies and the management of long-term conditions had become ‘over-professionalised’. This included a failure to support the overwhelming contributions of lay and self-care by individuals, family, friends and communities.

In addition, the limitations of the original ‘sanitary idea’ that drove public health in the nineteenth century have become apparent. Dumping sewage and chemical waste into the rivers and building tall chimneys to move air pollution beyond the city limits may solve problems in the short term but over time have soiled our planetary nest and contributed to global warming.

The new Public Health that has emerged during the past 30 years emphasises the ecological nature of the challenge and stresses the need for us to live sustainably in the habitats that nurture and protect us. This thinking has reconnected public health to town planning, which was akin to a Siamese twin in previous times.

Four principles of ecological town planning have been identified:

- Minimum intrusion into the natural state with new developments and restructuring reflecting and respecting the topographic, hydrographic, vegetal, and climatic environment in which it occurs, rather than imposing itself mechanically on locations.

- Maximum variety in the physical, social and economic structure and land use, through which comes resilience.

- As closed a system as possible based on renewable energy, recycling and the ecological management of green space.

An optimal balance between population and resources to reflect the fragile nature of natural systems and the environments that support them. Balance is required at both administrative district and neighbourhood levels to provide high-quality and supportive physical environments as well as economic and cultural opportunities (1)

This understanding has informed the development and adoption of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals to be attained by the year 2030, to which the British government is a signatory. And while government endorsement is needed to achieve these ambitions, concerted action from public authorities is also essential. (1)

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

- No poverty

- Zero hunger

- Good health and wellbeing

- Quality education

- Gender equality

- Clean water and sanitation

- Affordable and clean energy

- Decent work and economic growth

- Industry, innovation and infrastructure

- Reduced Inequalities

- Sustainable cities and communities

- Responsible consumption and production

- Life below water

- Life on land

- Peace, justice, and strong institutions

- Partnerships to achieve the goals.

The unsustainable path being followed in health and public health – in the face of rapidly increasing demand and an ageing population – was recognised in the UK in 2002. At that time, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, invited banker, Derek Wanless, to review the case for bringing NHS funding up to the level of comparable European countries. To support the case for increased funds, Wanless and his team examined three scenarios based on: the status quo; the implementation of evidence-based best practice universally across the present system; and the transformation of the NHS by grounding it in public health and full public engagement.

Only the third scenario would justify increased funding – under scenarios one and two the NHS was predicted to fall as quickly as 20 years time. Sadly, the significant increase in funds subsequently made available over those 20 years was appropriated into a new hospital-building programme and large pay increases for NHS staff without the transformation envisaged. Now in 2024, a combination of these flawed decisions with the aftermath of the pandemic has brought the situation to a head. Time is short and the need for real change

is urgent. However, our experience of the Covid-19 pandemic resonates with the cholera pandemics of the nineteenth century in that we have an opportunity to learn from it and build on the responses that were made.

The organised efforts of society for public health in Reading

In recent years, the World Health Organisation has advocated a comprehensive set of ten functions seen as necessary to deliver a robust public health response:

- Surveillance of population health and wellbeing (intelligence)

- Monitoring and response to health hazards and emergencies (health emergency planning)

- Health protection, including environmental, occupational, food safety and other threats

- Health promotion including action to address social determinants of health and health equity

- Disease prevention including the early detection of illness

- Assuring governance for health and wellbeing

- Assuring a sufficient and competent public health workforce

- Assuring sustainable organisational structures and finance

- Advocacy, communication, and social mobilisation

- Advancing public health research to inform effective intervention.

Under the Health and Social Care Act of 2012, the Director of Public Health is accountable for the delivery of their authority’s public health duties and is an independent advocate for the health of the population, providing leadership for its improvement and protection.

The Director of Public Health is a statutory officer of their authority and the principal adviser on all health matters to elected members and officers. They have a leadership role spanning the three domains of public health – health improvement, health protection, and population health care – and, therefore, are holders of politically restricted posts by section 2(5) of the Local Government and Housing Act 1989, inserted by schedule 5 of the 2012 Act.(4)

The statutory functions of the Director of Public Health include several specific responsibilities and duties arising directly from Acts of Parliament – mainly the NHS Act 2006 and the Health and Care Act 2012 – and related regulations. Some of these duties are closely defined but most allow for local discretion in how they are delivered.

The Director of Public Health’s most fundamental health protection duties are set out in law and are described below. How these statutory functions translate to everyday practice depends on a range of factors that are shaped by local needs and priorities over time.

Section 73A(4) of the 2006 act, inserted by section 30 of the 2012 Act gives the Director of Public Health responsibility for:

- All of their local authority’s duties are to improve the health of the people of their area.

- Any of the Secretary of State’s public health and health improvement functions that he or she delegates to local authorities, either by arrangement or under regulations – these include services mandated under regulations made under section 6C of the 2006 Act, inserted by section 18 of the 2012 Act.

Health protection-mandated functions include:

- Director of Public Health exercising their local authority’s functions in risk assessing, planning for, and responding to, emergencies that present a threat to their area’s public health.

- Preventing and controlling incidents and infectious disease outbreaks to protect their population.

- Carrying out public health aspects of the promotion of community safety.

- Taking local initiatives that reduce the public health impact of environmental and communicable disease risk.

The Director of Public Health has an overarching duty to ensure that the health protection system works effectively to the benefit of its local population.

From time to time, other responsibilities are placed upon the public health function within the local authority, including those directed to the deployment of the centrally provided public health grant.

At the moment, one such responsibility is that of collaborating with the NHS England and NHS Improvement approach to support the reduction of health inequalities. ‘Core 20 Plus 5’ identifies the most deprived 20% of the population as the focus for action together with five clinical priority areas:

- Maternity

- Severe Mental Illness

- Chronic respiratory disease

- Early cancer diagnosis

- Hypertension case finding.

A vision for public health in Reading

Reading Borough Council is committed to improving the health of everyone in the borough.

This commitment is captured in the Berkshire West Health and Wellbeing Strategy for 2021-2030, which has been adopted by the council.

This strategy sets out how the three Berkshire West local authorities, the Integrated Care System and other partners will work together to help people live healthier and happier lives.

Our priorities

The strategy’s vision is ‘Longer, Healthier and Richer lives for all’ and it has five jointly agreed priorities (with specific actions under each area):

- Reduce the differences in health between different groups of people.

- Support individuals at high risk of bad health outcomes to live healthy lives.

- Help children and families in their early years.

- Promote good mental health and wellbeing for all children and young people.

- Promote good mental health and wellbeing for all adults.

Whilst there are specific priorities contained within this strategy, our ambition is to embed prevention in all that we do. We will achieve this by adopting a public health approach, for each of the five identified priorities. The Reading public health team is committed to:

- Protecting and improving health by developing and supporting population-level interventions that are based on high-quality intelligence and evidence.

- A place- and asset-based approach to working with local communities and developing a community- orientated health and social care system, building on existing strengths to create a sustainable future.

- Maintaining a relentless focus on reducing health inequalities.

- Working with all those who value the health and wellbeing of the people of Reading.

- Commissioning and delivering evidence-based high-quality public health services that provide value for money.

We will:

- Assess the current provision and gaps in services compared to national guidance or best practices. This ensures the strategy co-ordinates with, and complements, others across the system. Specific issues include:

- Strengthening the arrangements for health protection in the borough

- Climate change impacts and risks

- A whole-systems approach to a healthy Reading

- A whole-schools approach to the health of children and young people

- Food access and sustainability

- The health of refugees and asylum seekers

- Improving access to general practice and NHS dentistry.

- Measure success by developing a robust outcomes and indicators framework. This will be presented as outcomes when measuring progress (including the direction of travel and targets), allowing us to focus on issues more sharply.

- Review evidence to understand ‘what works’ and identify opportunities for improvement.

- Consult stakeholders for their input on annual implementation plans.

- Identify resources for implementation, and co-ordinate actions at a whole-systems level in Berkshire West.

The strategic context

Reading Borough Council has established a Public Health Board, which will make a significant contribution to the health and wellbeing of Reading.

The board will oversee how the public health grant (from the Office of Health Improvement and Disparities – OHID) is invested, provide guidance and direction to the local council and its associated bodies and report to the Health and Wellbeing Board.

The board’s objectives include:

1. Identifying and establishing public health priorities and outcomes for Reading, as determined by the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment and Health and Wellbeing Strategy.

2. Overseeing the use of the ring-fenced public health grant and ensuring it meets its conditions. This includes monitoring grant-funded programme delivery across the council and related bodies and assessing the need, outcomes and evidence of clinical- and cost- effectiveness. outcomes and evidence of clinical- and cost-effectiveness.

3. Fostering partnerships across various council directorates.

4. Collaboratively exploring opportunities to influence the council’s partners within the broader public health system.

The way ahead

The strategic priorities set out in this year’s report form the basis of our delivery plans and work with other council directorates and external bodies over the next three years. They can’t be set in stone as they will need to change and evolve in response to threats to health and the changing needs of the population, changes in national policy and local priorities.

Where are we now?

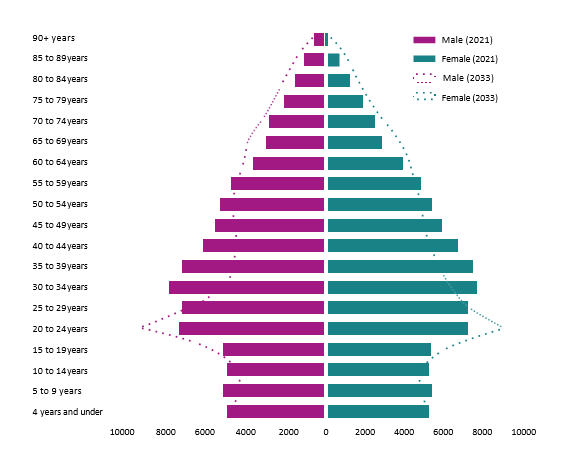

The population of Reading is relatively young and richly diverse when compared with the rest of England. It has grown faster than the national population and has a higher proportion of children and those in midlife than in England. The proportion of older people has increased also but not as much as in England.

The number of households has also increased. They tend to be multiple-occupied and, when compared with England, have become more ethnically diverse with fewer people who specify English as their main language.

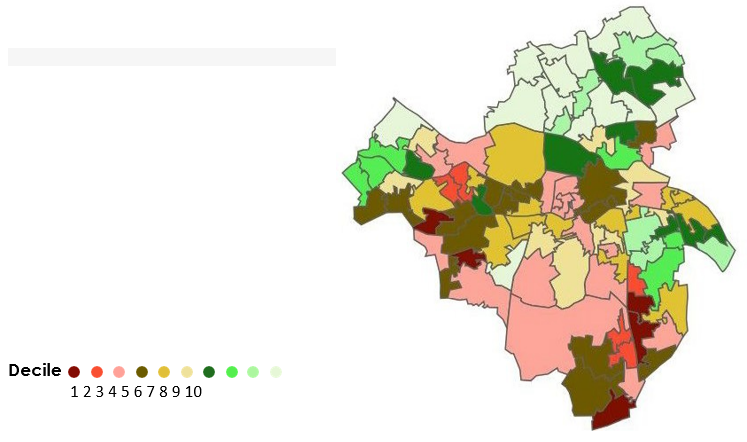

Reading has slightly less economic deprivation than England as a whole but shows clear signs of inequality in outcomes. For example, women in Reading do not enjoy the same life expectancy as those in the rest of the country.

This highlights the challenge facing us if we are to reduce the significant inequalities in health. It requires us to address both risk factors and risk conditions to support healthy, long lives.

Figure 1 – 2021 ‘Population Pyramid’ for Reading. This shows the structure of the population by age group and how the distribution of age is expected to change by 2033.

Source: 2021 Mid-year population estimates – ONS

Figure 2 – 2019 deprivation map by area of Reading. The key shows 1 as the most deprived and 10 as the least.

Source: English Indices of Deprivation 2019 – GOV.UK

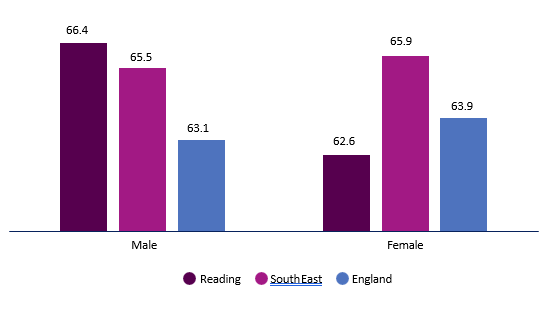

Figure 3 – Inequality in life expectancy.

Source: Inequality in life expectancy 2018-20 OHID Fingertips tool

Average life expectancy at birth for women is 82.3 years

Average life expectancy at birth for men is 79.0 years

Women living in the more affluent 20% of the area can expect to live 7.8 years longer than those in the 20% most deprived areas

Men living in the more affluent 20% of the area can expect to live 6.8 years longer than those in the 20% most deprived areas

Figure 4 – Healthy life expectancy at birth in Reading compared with South East and England 2018-20

Key stats

- +11% Reading population up from 155,700 in 2011 to 174,200 in 2021 – up 11% from national average.

- 67.1% of people in Reading were classified as white and 30% as Asian, Black, or Mixed Minority ethnic group.

- 81.1% of people in Reading specified English as their main language compared with 90.8% in England.

- 32.2% of households were classified as deprived on one dimension of deprivation (education, employment, health, or housing).

- 79.0 In 2018-20, the life expectancy for males was 79.0 years, which is comparable to England at 79.4 years, and for females it was 82.3 years, which is slightly lower than England at 83.1 years.

- -6.8 Male life expectancy in the most deprived areas was 6.8 years lower than in the least deprived areas compared with England where the difference between the most and least deprived males is 9.7. Female life expectancy between the most and least deprived residents differed by 7.8 years compared with 7.9 years in England.

Section One: Health Protection

Overview

Health protection aims to prevent, assess, and mitigate risks and threats to human health. These risks come from communicable diseases and exposure to environmental hazards such as chemicals and radiation.

It should be noted that the definition used in this report also extends to a wide range of additional threats, including those from commercial activities and violent behaviour.

The effective delivery of local health protection requires close partnership working between Reading Borough Council, West Berkshire Council, Wokingham Council, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), and other

local, regional, and national agencies and bodies, including voluntary community sector partners, the Thames Valley Local Resilience Forum and the NHS.

Over the past four years, the national and local health protection response has been in the spotlight due to the Covid-19 pandemic. During this period, we have built up expertise, developed relationships and

established systems to ensure an effective response to Covid-19 and other health protection threats. Building trust amongst our communities and working in partnership has been essential to providing an effective response.

Covid-19 is still circulating in the community, albeit in a more controlled manner, and the resurgence of other viral and respiratory illnesses, including influenza, is putting pressure on health and healthcare systems.

Additionally, local authorities are working to ensure they play their part in mitigating the impact of the commercial determinants of health and climate change with the sustained long-term threat to human populations and our ecosphere. Air quality in Reading continues to improve even after discounting the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on air quality trends.

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed and made existing inequalities worse and has especially affected already vulnerable communities. This includes the challenge of low vaccine uptake, which impacts on vulnerable population groups such as migrants, and those in the criminal justice system, with substance and alcohol misuse and those who are experiencing homelessness.

Where are we now?

Overall, health protection work in Reading has achieved some success.

For example, the uptake of NHS health checks for preventable disease detection is above the national average, and the rate of domestic abuse appears to be lower than the national average. And, while Reading experiences higher rates of some life-limiting diseases, evidence shows people take up support when it is available.

However, some areas require further action. Drug misuse deaths are slightly higher than the national average and Reading has a higher rate of violent crime and violent sexual offences compared to national rates.

With an estimated 20,000 smokers in Reading, tobacco control and smoking cessation remain high priorities. Smoking rates among manual and routine occupations in Reading are the third highest in the country, which is reflected in a higher lung cancer mortality rate compared to England.

Immunisation

Where are we now?

Reading compares well with England as a whole in terms of childhood vaccination uptake. However, some neighbourhoods and communities fall below the minimum levels needed to achieve ‘herd immunity’, which has a protective effect for everybody.

Childhood vaccinations for diseases including diphtheria and measles achieve high coverage – close to or exceeding the national average – while HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccination uptake, particularly among girls, is notably strong in Reading compared to England.

Vaccination coverage rates for adults aged 65 and over against pneumococcal disease in Reading is 70.8% in 2022/23 slightly lower compared with England (71.8%).

Another area where vaccine coverage is low among adults in Reading is Shingles. Between 1st April 2022 to the end of March 2023, uptake in Reading was below the regional average in both measured cohorts (aged 71 years and aged 75 years) and performing under the national average for aged 71 years. However, rates are in line with the national average for 75 years.

However, improvement is needed in some areas. Flu vaccination rates are similar to the national average but could be higher, especially among younger adults who are considered at clinical risk.

Key stats:

- 91.9% of babies aged one year in Reading were vaccinated against diphtheria, whooping cough, polio, meningitis, and pneumonia.

- 90.7% of two-year-olds in Reading were vaccinated against measles, mumps and rubella (MMR, one dose), compared with the England average of 89.3%. At five years of age, uptake for one dose was 93.5%, and 84.4% for two doses compared with 92.5% and 84.5% for England.

- 82.9% of girls aged 12-13 in Reading received one dose of the HPV vaccination, which helps protect against cervical and some other cancers.

- 95.2% of boys and girls aged 14-15 in Reading had received the MenACWY (meningococcal bacteria strains A, C, W and Y) vaccination, which helps protect against meningococcal meningitis, compared with 79.6% in England.

- In 2020/21, 71.1% of adults aged 65 and over in Reading received the PPV pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, which helps protect older people against diseases including bronchitis, pneumonia, and septicaemia.

- 49.1% of residents at clinical risk under age 65 were vaccinated against influenza.

What we will do

We have started work on a Health Needs Assessment to better understand vaccine hesitancy at a local level. This will help us focus initiatives on improving vaccine uptake in Reading. This will cover all cohorts, including seasonal vaccinations.

Drugs and alcohol

Where are we now?

Health protection also applies to protecting the population against threats and hazards arising from the social, physical and economic environment, including those that are commercially influenced and determined.

Existing public health programmes, including smoking cessation and the provision of drug and alcohol services, have begun to address some of these threats to health but more needs to be done. Problematic drug and alcohol use is often associated with homelessness, poor mental health, unemployment, domestic abuse, and ill health. The impact is not only felt by the individual but also by families, friends and communities.

In Reading, we have an ambition to support sustained recovery, thereby reducing harm to individuals and the wider community. Over the past few years – in response to the new national 2020 Drug and Alcohol strategy ’Harm to Hope’– there has been significant action around drug and alcohol use.

The public health team has:

- Completed a drug and alcohol needs assessment.

- Established a Drug-Related Death Forum – a multi-disciplinary panel, involving all partners to review the data and learning from drug and alcohol sudden deaths.

- Contributed to the national drug strategy, which requires local areas to establish a Combating Drugs Partnership (CDP). The Berkshire-wide CDP brings together relevant organisations and key individuals and provides them with proactive oversight of the implementation of the strategy’s priorities.

- Established the Berkshire Local Drug Information System – a multi-disciplinary panel that uses existing local expertise and resources to manage warnings regarding new, novel, potent, adulterated and contaminated drugs.

- Secured funding for a Multiple Disadvantage Outreach Team. This generated over £2.5m of investment in Reading between 2022-25, to help people sleeping rough who are dependent on drugs or alcohol. The funding was from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and Department of Health and Social Care, via the Rough Sleeper Drug and Alcohol Treatment Grant.

- Used the Supplementary Substance Misuse Treatment and Recovery Grant to improve the criminal justice response to drug dependence. The aim is to increase the number of treatment places and improve the quality of treatment, increase access to rehabilitation resources and reduce drug-related deaths.

- Worked with South Central Ambulance Service to distribute naloxone – the emergency antidote for overdoses caused by heroin and other opiates or opioids.

- Commissioned the Dame Carol Detoxification Service – a residential detox unit – as part of the Central South Coast Consortium.

What we will do

Over the next four years, we must ensure residents can access a responsive drug and alcohol treatment service. The early preventative treatment of drug and alcohol use will be a priority to enable us to become more efficient and effective and avoid the damage of long-term dependency.

To achieve this, we will:

- Commission drug and alcohol treatment services that are based on the best available evidence and good practice to improve the take-up and outcomes of these services.

- Commission a pilot service in 2024-25 that offers Buvidal as an alternative to prescribed substitute medication to support the withdrawal from opioids. Buvidal is used to treat opioid dependence in patients who are also receiving medical, social and psychological support.

- Reduce drug-related deaths. The increase in the use of synthetic opioid drugs has been identified as a national, regional and local issue. Synthetic opioids pose an increased risk of harm as they are more potent than heroin. To address this challenge, we plan to:

- Improve the timeliness of intelligence from forensic toxicology to prevent further drug-related harm.

- Improve our understanding of the local drug markets.

- Improve communications with the South Central Ambulance Service and the Royal Berkshire Hospital concerning overdoses and near misses.

- Issue quicker and more accurate drug alerts through the current local drug information system process.

- Increase the availability of naloxone – a medication that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose – in pharmacies and public spaces where drug taking is prevalent.

In 2024-25 we will:

- Develop and implement a strategic drug and alcohol delivery plan.

- Collaborate with our system partners to procure a Berkshire Individual Placement and Support Scheme (IPS). This will improve the employment prospects of those with complex needs, and drug and alcohol problems.

- Contribute to a project that explores the options for a Berkshire Family Drug and Alcohol Court (FDAC).

- Work collectively to plan and ensure better-integrated services. The aim is to prevent people with substance misuse issues from falling through gaps in the system and maximise the benefits of using services. These people also often have physical and mental health needs and are unemployed or homeless.

- Invest in an outreach worker as part of the young people’s treatment services.

- Use the Supplemental Substance Misuse Treatment and Recovery Grant to implement a lived experience recovery organisation model. This model ensures that peer-based support services and communities of recovery are linked to and embedded in drug treatment systems.

Other health protection work

The Berkshire West Health Protection and Resilience Partnership Board (HPRPB) has been formed to protect and safeguard the health of residents across Berkshire West (West Berkshire, Wokingham, Reading). The HPRPB is chaired by the Wokingham Director of Public Health and reports every quarter to the Health and Wellbeing Boards for West Berkshire, Wokingham, and Reading. It will also report annually offering a clear analysis of risks, mitigation efforts, and incidents to both the BOB Integrated Care Board Unified Executive and the three health and wellbeing boards.

The Berkshire Health Emergency Planning Group (HEPG) has been reinstated since the pandemic as a dedicated health forum for responders, focusing on health-related emergency preparedness, response and recovery within Berkshire. The group’s goals include preparing, reviewing and ensuring the robustness of health-related plans and arrangements. This involves fostering co-operation, liaison and information sharing among the six Berkshire unitary authorities and other health partners. Collaboration extends to health-related emergency planning, aligned with national and Thames Valley arrangements to prevent duplication. A task and finish group, led by the Interim Consultant in Public Health, has reviewed the group’s work plan for 2023–2024.

The Reading Interim Public Health Protection Principal has formed a health protection practitioner group to standardise health protection across Wokingham, Reading and West Berkshire. This collaborative effort with the Interim Consultant in Public Health helps spread best practice, skills, capacity building, professional development and peer support.

The remit of the Berkshire HEPG is to:

- Provide a specific health forum for responders who may be required to work together concerning health- related emergency preparedness, response and recovery within Berkshire.

- Prepare and review health-related plans and arrangements, and ensure they are robust and fit for purpose.

- Encourage appropriate co-operation, liaison and information sharing across the footprint of the six Berkshire unitary authorities and other health partners. This applies to health-related emergency planning preparedness and response at all levels, complementing national and Thames Valley arrangements and avoiding replication.

- To review lessons learned from incidents, training and exercises and incorporate them into relevant plans and procedures.

Section Two: Health Improvement – Adults

Overview

Reading Borough Council’s goal is to help people stay healthy through adulthood and into later life. We aim to support people’s mental and physical wellbeing and reduce dependency on statutory services by working with local communities and encouraging healthy behaviours through adulthood.

Achieving this depends on a range of factors, from biological inheritance to physical, social, economic and environmental influences and behavioural choices.

We want to create conditions that promote health and avoid risk behaviours that cause ill health – all underpinned by access to high-quality clinical and social care services.

Effective action in these areas can minimise the impact of the major causes of physical and mental ill health, including communicable diseases, anxiety, depression, musculoskeletal problems, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancers.

Adults receive support through a range of public health programmes and other council services, such as NHS health checks, stop-smoking programmes, services for managing a healthy weight and for those who require support to address alcohol and drug problems.

These involve the council and NHS working in partnership with local communities and a range of statutory and voluntary agencies to ensure that interventions promote health and wellbeing at a neighbourhood level.

Healthy weight

Where are we now?

Reading Borough Council implements a range of universal programmes that aim to help everyone in Reading maintain a healthy weight

Our work includes:

- Promoting physical activity, leisure and green spaces – via the newly-formed Physical Activity Alliance in Reading.

- Employing a community food worker to collaborate with the voluntary and community sector and engage the local population. The role focuses on improving access to healthy foods, supporting people to move more and promoting health and wellbeing. It also helps educate local people on issues related to cooking healthily and growing food.

- The community food worker played a key role in in the launch of Reading Food Partnership in May 2024. This Reading-focused website is a one-stop shop for support and information about eating well, aimed at people particularly affected by the cost of living.

- We aim to widen the remit of the role to focus on food poverty and how this impacts access to healthy foods.

- The Healthwise physical activity referral programme and cardiac referral pathway through the GLL (Greenwich Leisure Ltd) leisure contract. This supports people with long-term conditions, weight management issues and low confidence.

- Organising group walks around the town. These walks promote physical activity and connection with nature and community. You can find out more on the Reading Borough Council website.

- A reconditioning programme, delivered by Get Berkshire Active to increase physical activity in older people.

- A Healthy Weight Needs Assessment, which allowed us to gain a better understanding of current needs and the impact of Covid-19 on the issue of excess weight. Produced with potential service users and system partners who make referrals, it explored the impact of the cost of living, access to healthy food, physical activity and weight management support.

We also operate programmes that aim to support specific sections of the local population – also known as tier two services.

Healthwise, operated by GLL (Greenwich Leisure Ltd), is a 12-week adult weight management programme, which includes physical activity, behaviour change strategies and nutrition support. It also allows participants to access the gym during the programme and provides discounted entry to leisure facilities for two years.

We have also received funding from the Office of Health Development and Disparities (OHID) to help deliver other tier two weight management services targeted at ‘seldom-heard groups’.

This refers to under-represented people who use, or might use, health or social services and are less likely to be heard by these service professionals and decision-makers.

As part of this work, we commissioned Slimming World to deliver a programme addressing diet, physical activity, and behaviour change among people most at risk of obesity and who are typically less likely to engage with services. These include:

- People diagnosed with long-term health conditions, including mental health conditions

- People with learning disabilities

- Men

- Black and minority ethnic groups

- Other seldomly heard community groups.

What we will do

On the issue of weight management, primary prevention means focusing on the wider commercial determinants of health, in addition to campaigns that encourage healthy eating and physical activity. A whole-systems approach will address the structural and policy barriers to good health and aim to reverse the rise of excess weight in the population of Reading.

We will collaborate with people living with excess weight and colleagues in the council, primary care, the integrated care system and the voluntary and community sectors to share the findings of the Healthy Weight Needs Assessment. The aim is to:

- Adopt and establish a whole-system approach with upstream primary prevention that embodies a compassionate approach and addresses the stigma attached to overweight and obesity.

- Establish a Reading Food Partnership, led by a range of partners. This will take a broad approach to food security, health and sustainability, with a focus on ensuring high-quality nutritious food for all.

- Commission a holistic service that provides longer-term support for targeted groups and reflects the diversity and vibrancy of Reading.

Smoking cessation

Where are we now?

In Reading, 14.4% of people smoke, which is similar to the England average and part of a general downward trend. However, this rate obscures prevalence between routine and manual groups, placing Reading amongst the highest rates in the country for this group. People in this group are over four times more likely to be smoking tobacco. It also highlights the steep social gradient that exists in Reading and so smoking cessation remains central to the prevention and reduction of health inequality There is significant variation in smoking prevalence from ward to ward. These range from 10% in Peppard Ward, (equivalent to 760 smokers), to 18.0% in Katesgrove Ward (1,880 smokers).

Aside from the geographical variation, there are greater differences between population groups. For example, people employed in routine and manual occupations in Reading are over four times more likely to be smokers than those employed in other occupations. The rate among people in treatment for substance misuse is even higher – 82%. Supporting people to quit smoking and preventing young people from taking up smoking are priorities if we are to reduce the harm caused by tobacco.

Smokefreelife

Smokefreelife Berkshire is the local NHS stop-smoking service that serves Reading and Berkshire West. Any adult or young person who wishes to quit smoking can contact them for free, confidential advice and support.

Nicotine is highly addictive, and many people find that trying to quit on their own is extremely difficult and that it takes many attempts before they achieve it. The most effective way is to get support from an NHS

stop-smoking service. This helps people manage nicotine cravings along with a nicotine replacement therapy to suit individual needs. The evidence shows that smokers are up to four times more likely to quit using this method, than by ‘going it alone’.

In 2021-22, Smokefreelife Berkshire helped 364 Reading residents quit smoking. This represents nearly 60% of smokers who set a date to quit smoking.

Smokefreelife Berkshire also:

- Provides training throughout the year to NHS staff and other professionals, such as drug and alcohol treatment providers and social care staff. This gives them the knowledge and skills they need to talk to people about their smoking and to signpost them to the service.

- Produces regular tailored communications, via social media and local networks, to support national campaigns such as Stoptober, No Smoking Day and other key events such as Ramadan. They have created a video for clinicians and regularly share case studies of people who have successfully quit smoking.

- Provides regular outreach at community venues – including Reading College, Morrissons Basingstoke Rd, Lidl Oxford Rd and Broad St Mall – and set up new clinics at Emmer Green Surgery and South Reading Leisure Centre.

- Attends local events – for example, Southcote Wellbeing Day, Waterfest and coffee mornings held at Reading Central Library – to welcome newcomers to the town.

Smoking cessation in the NHS

Our partners in the NHS also have a clear remit to support and reduce the prevalence of smoking by increasing the number of people who access support. This forms part of the Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West Integrated Care Board (BOB ICB) Joint Forward Plan. The ambition is that NHS-funded treatment services are offered to all in-patients, pregnant women and their partners, long-term users of specialist mental health services and those in learning disability services.

So far, over 75% of all pregnant women who smoke are routinely seen by a tobacco dependency advisor as they book into the maternity clinic at the Royal Berkshire Hospital. They are offered specialist support every week along with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). A tobacco dependency advisor is also active at Prospect Park Hospital to ensure that patients who smoke can access specialist stop-smoking advice and NRT during their stay.

Smokefree Sidelines

Smokefree Sidelines (SFS) is an initiative that aims to prevent young people from taking up smoking by changing social norms linked to smoking, vaping and work. One of the ways it aims to achieve this is by encouraging people not to smoke or vape next to outdoor spaces used by children – namely football pitches. In the 2022-23 season, two Reading youth football clubs, AFC Reading and Elite FC both signed up to take part along with 17 clubs from across Berkshire West and others from Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire.

The initiative was publicised on the Berks and Bucks FA website and many clubs added information and links to this from their sites. Local press releases were picked up in Bracknell, Newbury and Reading.

The Smokefree Sidelines Podcast (on YouTube) was created by partners and sent to all youth football clubs in Berkshire West that belong to the Bucks and Berks FA. Supporting resources, including banners, selfie boards and flags, were provided to participating clubs.

The evaluation of Smokefree Sidelines found that:

- Coaches understood the importance of de-normalising smoking behaviour and identifying secondary benefits of non-smoking environments. This includes spectators being less exposed to second-hand smoke and the potential to improve health outcomes for smoking spectators.

- Parents and carers believe that youth football has a role to play in promoting healthy lifestyles to young players.

- Many parents had witnessed smoking and vaping on the sidelines. Most respondents stated that they had noticed fewer people smoking on the sidelines at home matches when the campaign resources were in use and the intervention was live. This suggests that, overall, the intervention had a positive impact.

- An expansion of the Smokefree Sidelines initiative into more youth football clubs and other youth team sports, such as rugby and hockey, could play an important role in de-normalising smoking and vaping around children in public open spaces.

What we will do

Prevent the inflow of young people recruited as smokers and vapers

It is estimated that over 80% of smokers took up the habit before the age of 20 and became addicted to nicotine in their teenage years. The advent of e-cigarettes or vapes is another route by which young people can become addicted to nicotine. They have a growing popularity with some young people. From 2022 to 2023, the rates of experimentation with e-cigarettes amongst 11-17-year-olds increased from 15.8% to 20.5%.

All Reading secondary schools have been provided with resources and lesson plans to support teachers in delivering health education around smoking and vaping to pupils, as part of personal, social and health

education (PSHE) lessons. All schools have been provided with the latest advice and guidance on managing vapes in schools and lesson plans that provide pupils with the facts about smoking and e-cigarettes.

The annual school survey on smoking and drinking was sent to all secondary schools in January 2023. Data from the survey provides insight into the behaviours and beliefs of 11-17-year-olds and about smoking and vaping at a local level. The survey enables schools and other partners to focus on preventing young people from taking up smoking or vaping. It also informs the Berkshire West Tobacco Control Alliance about how best to co-produce smoking and vaping resources with young people.

Protecting families and communities from tobacco-related harm

Creating smoke-free environments in which people live, work and play is an important way to protect families and communities from tobacco-related harm.

Children and young people are at risk the more they are exposed to smoke and by the acceptance of smoking in our society. Furthermore, young people are most at risk of becoming smokers themselves if they grow up in communities where smoking is the norm.

Despite the significant progress made through legislative changes, such as the ban on smoking in public places in 2007, families and communities are exposed to tobacco in many ways. This is especially true amongst populations where the rates of smoking are disproportionately high – for example, routine and manual occupations, people with severe mental illness, people who live in rented accommodation, people who are homeless or in treatment for substance misuse, young leavers of care and young offenders.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the Community Wellness Outreach Service

Where are we now?

The Community Wellness Outreach Pilot aims to provide access to an enhanced NHS Health Check for people in under-served population groups who may be at risk of cardiovascular disease and poor mental health. These checks are provided in non-clinical settings and provide appropriate care. Where necessary, this includes onward referral by using social prescribing to put people in touch with activities that will improve their physical and mental health.

In partnership with the BOB Integrated Care Board, the Reading Integration Board including the public health team has commissioned Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust’s ‘Meet PEET (Patient Experience Engagement Team) and Reading Voluntary Action to deliver this service in community settings across Reading. The service aims to engage groups who are disproportionately affected by cardiovascular disease and under-served by the current universal NHS health check offer.

Working with partners in the voluntary, community and social enterprise sectors, the engagement programme will ensure that the Community Wellness Outreach Service reaches the priority groups. It is underpinned by an asset-based approach that links the service and participants with existing community resources, networks and assets. This will avoid placing demand on primary care and help sustain community assets.

The community engagement work will also lead to a better understanding of the barriers that priority groups face in gaining access to universal services. Feedback will be used to improve the service and ensure that the offer is accessible to those who need it most.

What we will do

Reading Borough Council plan to build on their existing partnership with Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust to deliver enhanced CVD health checks within both organisation’s workplaces.

The delivery plan for this pilot project comprises two elements:

- To scale up the existing NHS Health Check to include people aged over 30.

- To offer NHS health checks to employees within Reading Borough Council workplaces.

Sexual health

Reading Borough Council’s public health team jointly commissions integrated services that promote good sexual and reproductive health for Reading, West Berkshire and Wokingham.

These offer advice, information, education and treatment services related to contraception and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Failure to provide these services can lead to unplanned pregnancies, abortions, psychological harm from sexual abuse, the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and potential complications, such as pelvic inflammatory disease.

Everyone who is sexually active is at risk of an STI. However, some groups are at higher risk, including young people, individuals from some black and ethnic groups, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and those living in socially or economically disadvantaged areas. In Reading, young people are 10% of the population but have the highest rates of STI diagnoses and represent a significant percentage of new STI cases.

Where are we now?

Data from integrated services shows that levels of sexual disease appear to be lower than in England. Recorded rates of new sexually transmitted infections in Reading are lower than the national average, but continued efforts are needed to maintain this positive trend and there remains a clear lag in the timely diagnosis of HIV.

Reading’s key stats:

- The rate of all new STI (sexually transmitted infection) diagnoses (excluding chlamydia in under 25s) in Reading was 559 per 100,000 population in 2023 (which is significantly higher than the England rate of 520 per 100,000 population.

- The chlamydia detection rate among young people aged 15-24 was 1,288 per 100,000, lower than the England rate of 1,546 per 100,000.

- In 2022, 11 new cases of HIV were diagnosed. There were also 335 people aged 15-59 living with HIV. The diagnosed prevalence rate was 2.94 per 1,000 – higher than the rate in England (2.34).

In the past year, we extended the provision of emergency hormonal contraception (EHC) and long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) provisions. We have partnered with neighbouring local authorities to create a local sexual health action plan that outlines our main priorities. We are collaborating with our sexual health service provider to update the service to meet post-Covid needs, closely monitor service data and improve access to high-quality data.

Over the past year, we have worked with the voluntary sector organisations on campaigns to promote the importance of HIV testing and increase the number of tests that are carried out in Reading.

Working with our sexual health service provider, we are updating the service to meet the demands of the post-Covid-19‘new normal’, focusing on close monitoring and service improvement. This year they have revised their opening hours and have ensured that young people can access online STI testing.

Our focus for the next year is to review condom distribution, review and support women’s health hubs, and enhance links with substance misuse services and those supporting individuals with learning disabilities.

Additionally, we aim to improve data collection and update our sexual health needs assessment.

Services are delivered at the main Florey clinic in central Reading, and via outreach services across Berkshire. Services include:

- STI testing and treatment

- General education and information on safer sex practice

- Access to a range of contraception, including LARC methods

- Emergency contraception

- Support to reduce the risk of unplanned pregnancy

- Free pregnancy tests

- Appropriate onward referral to abortion services or maternity care.

What we will do

We will:

- Ensure access to sexual health services for everyone. This covers free STI testing and treatment, notification of infected persons’ sexual partners, free contraception and access to all methods of contraception.

- Support women of reproductive age to continue to have access to the full range of contraception in the setting that is most appropriate.

- Ensure residents have wider access to face-to-face and online STI testing.

- Enable integrated sexual health services to continue to be supporting wider safe sex educational campaigns and activity commissioned by the public health team.

- Provide young people with information, advice and services they need to make informed decisions about their sex lives, sexual health and wellbeing.

- Continue to work with providers and other partners to promote the importance of HIV testing and information and improve awareness and access to pre-exposure prophylaxis treatment (medication taken to prevent HIV).

- Continue to work with the service provider to assess and ensure the longer-term sustainability of the service in the face of increasing activity. This is taking the form of an ‘open-book’ approach to service finances and joint work on activity reporting.

- Work with our health colleagues across the ICB to develop an integrated whole-system approach to sexual and reproductive health.

- Explore options for expanding digital and remote access and online testing as an alternative access route for residents.

- Continue to offer accessible and timely provision of services (including pre-exposure prophylaxis treatment) through the Royal Berkshire Hospital NHS Trust.

- Work with our voluntary sector partners to identify barriers to accessing early HIV testing and deliver an awareness campaign to address these barriers.

Health and wellbeing – adults

When surveyed, adults in Reading report similar levels of wellbeing as the rest of the country. However, public health data shows that their mental health may not be as good – they also report lower levels of physical activity, eat less fruit and vegetables and carry more weight.

Prevalence of long-term conditions, such as depression, hypertension and diabetes, tends to be lower than in England, as is the rate of suicide. Deaths from cancer and admissions for self-harm were similar to the rest of the country but there are challenges for those growing old in Reading with higher levels of recorded falls and hip fractures.

The health of Reading – a snapshot:

- In the 2021 Census, 1% of residents in Reading described their health as “very bad” and 3.7% described it as “bad” a fall from 4.0% in 2011.

- In 2020-21, 69.7% of adults aged 18 and over were classified as overweight or obese (the rate for England was 63.8%). 33.5% of these adults were obese, it was 25.9% in England.

- In 2021-22, there were 315 emergency hospital admissions for self-harm in Reading.

- In 2020-22 there were 44 suicides in Reading; a rate of 9.2 per 100,000 (England – 10.3).

- In 2021-22, there were 1,989 hospital admissions for alcohol-related conditions. The admission rate was 1,493 per 100,000 (England – 1,734).

With partners, we have continued to monitor the five priority areas from the Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy and contributed to a range of health improvement projects. For example:

- Working to embed a community development approach to health improvement alongside partners including the Reading Sustainable Communities team, Adult Social Care colleagues and wider voluntary and community sector partners.

- The Reading Community Health Champions network, delivered in partnership with the Alliance for Cohesion and Racial Equality and the wider voluntary and community sector. This is a group of trained and trusted community volunteers, who connect communities to evidence-based health and wellbeing information, empowering them to champion their own health priorities.

- Embedding the findings of the 2021-22 Community Participatory Action Research report into local practice, and continuing to work with the University of Reading and community organisations to develop opportunities for community researchers.

- Supporting the Community Wellness Outreach project to bring NHS Health Checks and holistic wellbeing support to those who need it most, and aligning this work with ongoing health improvement programmes

- Working alongside the Social Inclusion Board to support place-based pilots in Whitley and Church wards, aiming to improve education and employment outcomes.

What we will do

- Continue to deliver the Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy for Reading with our council, community and system partners.

- Continue to support and implement the projects described above.

- Work more closely with council colleagues to ensure that a public health approach and the building blocks of good health are in place for everyone who lives in Reading.

- Deliver a Falls Prevention Programme through GLL. This aims to address falls risks and promote independence in older adults through a structured and evidence-based approach. By targeting strength, balance and mobility, the programme aims to enhance participants’ physical health, functional ability and quality of life. Ongoing exercise maintenance sessions will provide opportunities for long-term adherence and continued progress.

- A Falls Prevention Diagnostic review and needs assessment is currently underway in Reading. This aims to inform the design and development of a complete falls service and pathway.

Mental health – adults, children and young people

We promote a prevention approach to mental health, which means trying to stop mental health problems before they start.

The public health team collaborates with colleagues in Brighter Futures for Children and hosts the Reading Mental Health and Wellbeing Network to guide and monitor the Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy priorities 4 and 5 – promoting the mental health and wellbeing of children, young people and adults.

This includes co-ordinating support for those with poor mental health and enabling equitable access to mental health services.

We also promote an understanding of what leads to good mental health, such as adequate housing, access to lifelong education, worthwhile employment and opportunities to connect and participate with the community and neighbourhood. In addition, we promote self-care and personal resilience using national campaign resources such as Every Mind Matters.

Where are we now?

Reading’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Network facilitates a partnership approach to supporting the mental health of residents in Reading.

In the last year, this has included delivering programmes such as the Physical Activity for Mental Health (PAMH) Partnership.

The PAMH Partnership looks to break down the barriers between physical and mental health, an action outlined under priority 5 of the Health and Wellbeing Strategy. The public health team facilitated this partnership and through this project, 110 people from 39 organisations, including voluntary and community sector partners, took part in a range of training sessions.

Training included mental health first aid training, culturally tailored mental health awareness, walk leader training and coaching qualifications.

A key partner within the PAMH Partnership is Compass Recovery College, which not only attended training as part of the project but was a core training delivery partner.

Compass Recovery College sits within the public health team. The Compass team develop and deliver free mental health and wellbeing workshops and social drop-in sessions for anyone in Reading aged 18 or over who may be affected by mental health or wellbeing challenges. All workshops are co-produced by recovery workers, experts with lived experience, volunteers and mental health professionals.